ਆਰਥਰ ਸ਼ੋਪੇਨਹਾਵਰ

ਆਰਥਰ ਸ਼ੋਪੇਨਹਾਵਰ (/ˈʃoʊpənhaʊ.ər//ˈʃoʊpənhaʊ.ər/ SHOH-pən-how-ər; ਜਰਮਨ: [ˈaɐ̯tʊɐ̯ ˈʃoːpm̩ˌhaʊ̯ɐ]; 22 ਫਰਵਰੀ 1788 – 21 ਸਤੰਬਰ 1860) ਇੱਕ ਜਰਮਨ ਫ਼ਿਲਾਸਫ਼ਰ ਸੀ। ਉਹ ਆਪਣੀ 1818 ਦੀ ਰਚਨਾ ਦ ਵਰਲਡ ਐਜ਼ ਵਿਲ ਐਂਡ ਰੀਪਰੀਜੈਂਟੇਸ਼ਨ (1844 ਵਿੱਚ ਵਧਾਈ ਗਈ) ਲਈ ਮਸ਼ਹੂਰ ਹੈ। ਇਸ ਵਿੱਚ ਉਹ ਦਿੱਸਦੇ ਸੰਸਾਰ ਨੂੰ ਇੱਕ ਅੰਨ੍ਹੀ ਅਤੇ ਅਮਿੱਟ ਪਰਾਭੌਤਿਕ ਇੱਛਾ ਦੇ ਵਜੋਂ ਪਰਿਭਾਸ਼ਿਤ ਕਰਦਾ ਹੈ।[15][16] ਇੰਮਾਨੂਏਲ ਕਾਂਤ ਦੇ ਅਗੰਮੀ ਆਦਰਸ਼ਵਾਦ ਤੋਂ ਅੱਗੇ ਚੱਲਦਿਆਂ, ਸ਼ੋਪੇਨਹਾਵਰ ਨੇ ਇੱਕ ਨਾਸਤਿਕ ਪਰਾਭੌਤਿਕ ਅਤੇ ਨੈਤਿਕ ਪ੍ਰਣਾਲੀ ਨੂੰ ਵਿਕਸਿਤ ਕੀਤਾ ਜਿਸ ਦਾ ਦਾਰਸ਼ਨਿਕ ਨਿਰਾਸ਼ਾਵਾਦ ਦੇ ਇੱਕ ਮਿਸਾਲੀ ਪ੍ਰਗਟਾਵੇ ਵਜੋਂ ਵਿਖਿਆਨ ਕੀਤਾ ਗਿਆ ਹੈ,[17][18][19] ਜੋ ਜਰਮਨ ਆਦਰਸ਼ਵਾਦ ਦੇ ਸਮਕਾਲੀਨ ਪੋਸਟ-ਕਾਂਤੀਅਨ ਦਰਸ਼ਨਾਂ ਨੂੰ ਖਾਰਜ ਕਰਦਾ ਹੈ। [20][21]ਪੱਛਮੀ ਦਰਸ਼ਨ ਵਿੱਚ ਸ਼ੋਪੇਨਹਾਵਰ ਪਹਿਲੇ ਚਿੰਤਕਾਂ ਵਿਚੋਂ ਇੱਕ ਸੀ ਜੋ ਪੂਰਬੀ ਦਰਸ਼ਨ (ਜਿਵੇਂ ਕਿ ਸਨਿਆਸ, ਮਾਇਆ ਰੂਪੀ ਸੰਸਾਰ) ਦੇ ਮਹੱਤਵਪੂਰਨ ਸਿਧਾਂਤਾਂ ਨਾਲ, ਸ਼ੁਰੂ ਵਿੱਚ ਆਪਣੇ ਦਾਰਸ਼ਨਿਕ ਕੰਮ ਦੇ ਸਿੱਟੇ ਵਜੋਂ ਇਸੇ ਤਰ੍ਹਾਂ ਦੇ ਸਿੱਟਿਆਂ ਤੇ ਪਹੁੰਚਦੇ ਹੋਏ ਸਾਂਝ ਪਾਉਂਦਾ ਹੈ ਅਤੇ ਉਹਨਾਂ ਦੀ ਪੁਸ਼ਟੀ ਕਰਦਾ ਹੈ।[22][23]

ਆਰਥਰ ਸ਼ੋਪੇਨਹਾਵਰ | |

|---|---|

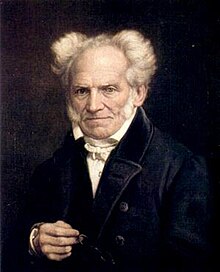

ਸ਼ੋਪੇਨਹਾਵਰ ਦੀ 1855 ਦੀ ਇੱਕ ਪੇਂਟਿੰਗ, ਕ੍ਰਿਤੀ: ਜਿਊਲਸ ਲੁੰਟੇਸ਼ੁਜ਼ | |

| ਜਨਮ | 22 ਫਰਵਰੀ 1788 ਡਾਨਜ਼ਿਗ (ਗਡਾਂਸਕ) |

| ਮੌਤ | 21 ਸਤੰਬਰ 1860 (ਉਮਰ 72) |

| ਰਾਸ਼ਟਰੀਅਤਾ | ਜਰਮਨ |

| ਸਿੱਖਿਆ | |

| ਕਾਲ | 19ਵੀਂ ਸਦੀ ਦਾ ਫ਼ਲਸਫ਼ਾ |

| ਖੇਤਰ | ਪੱਛਮੀ ਦਰਸ਼ਨ |

| ਸਕੂਲ | |

| ਅਦਾਰੇ | ਬਰਲਿਨ ਯੂਨੀਵਰਸਿਟੀ |

ਮੁੱਖ ਰੁਚੀਆਂ | ਮੈਟਾਫਿਜ਼ਿਕਸ, ਸੁਹਜ ਵਿਗਿਆਨ, ਨੀਤੀ, ਨੈਤਿਕਤਾ, ਮਨੋਵਿਗਿਆਨ |

ਮੁੱਖ ਵਿਚਾਰ | ਐਂਥਰੋਪਿਕ ਸਿਧਾਂਤ[6][7] ਐਟਰਨਲ ਜਸਟਿਸ ਲੋੜੀਂਦੇ ਕਾਰਨ ਦਾ ਸਿਧਾਂਤ ਦੀ ਚੌਗੁਣੀ ਜੜ੍ਹ ਹੈੱਜਹੋਗ ਦੀ ਦੁਬਿਧਾ ਦਾਰਸ਼ਨਿਕ ਨਿਰਾਸ਼ਾਵਾਦ ਪ੍ਰਿੰਸੀਪੀਮ ਇੰਡੀਵਿਜੂਏਸ਼ਨਿਸ ਹੁਕਮ ਵਸਤ ਆਪਣੇ ਆਪ ਵਿਚ ਵਜੋਂ |

ਪ੍ਰਭਾਵਿਤ ਕਰਨ ਵਾਲੇ | |

ਪ੍ਰਭਾਵਿਤ ਹੋਣ ਵਾਲੇ | |

| ਦਸਤਖ਼ਤ | |

ਭਾਵੇਂ ਕਿ ਉਸ ਦਾ ਕੰਮ ਆਪਣੀ ਜ਼ਿੰਦਗੀ ਦੌਰਾਨ ਮਹੱਤਵਪੂਰਨ ਧਿਆਨ ਹਾਸਲ ਕਰਨ ਵਿੱਚ ਅਸਫਲ ਰਿਹਾ ਸੀ, ਸ਼ੋਪਨਹਾਹੋਅਰ ਦੇ ਫ਼ਲਸਫ਼ੇ ਨੇ ਸਾਹਿਤ ਅਤੇ ਵਿਗਿਆਨ ਸਮੇਤ ਵੱਖੋ-ਵੱਖ ਵਿਸ਼ਿਆਂ ਤੇ ਮਰਨ-ਉਪਰੰਤ ਪ੍ਰਭਾਵ ਪਾਇਆ ਸੀ। ਸੁਹਜ-ਸ਼ਾਸਤਰ, ਨੈਤਿਕਤਾ ਅਤੇ ਮਨੋਵਿਗਿਆਨ ਬਾਰੇ ਉਸ ਦੀਆਂ ਲਿਖਤਾਂ ਨੇ 19 ਵੀਂ ਅਤੇ 20 ਵੀਂ ਸਦੀ ਵਿੱਚ ਚਿੰਤਕਾਂ ਅਤੇ ਕਲਾਕਾਰਾਂ ਉੱਤੇ ਮਹੱਤਵਪੂਰਨ ਪ੍ਰਭਾਵ ਪਾਉਣਾ ਸੀ। ਜਿਹਨਾਂ ਨੇ ਉਸਦੇ ਪ੍ਰਭਾਵ ਨੂੰ ਕਬੂਲਣ ਦਾ ਹਵਾਲਾ ਦਿੱਤਾ ਹੈ ਉਹਨਾਂ ਵਿੱਚ ਸ਼ਾਮਲ ਹਨ:ਫ਼ਰੀਡਰਿਸ਼ ਨੀਤਸ਼ੇ, ਰਿਚਰਡ ਵੈਗਨਰ, ਲੀਓ ਟਾਲਸਟਾਏ, ਲੁਡਵਿਗਵਿਟਗਨਸ਼ਟਾਈਨ, ਐਰਵਿਨ ਸ਼ਰੋਡਿੰਗਰ, ਕਾਰਲ ਹਾਈਨਰਿਖ਼ ਉਲਰਿਚਸ, ਓਟੋ ਰੈਂਕ, ਗੁਸਤਾਵ ਮਾਲਰ, ਯੋਸਿਫ਼ ਕੈਂਪਬੈਲ, ਐਲਬਰਟ ਆਇਨਸਟਾਈਨ,ਕਾਰਲ ਜੁੰਗ, ਥਾਮਸ ਮਾਨ, ਐਮਿਲ ਜ਼ੋਲਾ, ਜਾਰਜ ਬਰਨਾਰਡ ਸ਼ਾਅ, ਹੋਰਹੇ ਲੂਈਸ ਬੋਰਹੇਸ ਅਤੇ ਸੈਮੂਅਲ ਬੈਕਟ।

ਜ਼ਿੰਦਗੀ

ਸੋਧੋਆਰਥਰ ਸ਼ੋਪੇਨਹਾਵਰ ਦਾ ਜਨਮ 22 ਫਰਵਰੀ 1788 ਨੂੰ ਡੈਨਜ਼ੀਗ (ਹੁਣ ਗਡਾਂਸਕ, ਪੋਲੈਂਡ) ਵਿੱਚ ਇੱਕ ਖੁਸ਼ਹਾਲ ਵਪਾਰੀ, ਹੈਨਰਿਖ਼ ਫਲੋਰਿਸ ਸ਼ੋਪੇਨਹਾਵਰ ਅਤੇ ਉਸ ਦੀ ਉਸ ਨਾਲੋਂ ਬਹੁਤ ਛੋਟੀ ਪਤਨੀ, ਜੋਹਾਨਾ ਤੋਂ ਹੋਇਆ ਸੀ। ਸ਼ੋਪੇਨਹਾਵਰ ਪੰਜ ਸਾਲ ਦਾ ਸੀ ਜਦੋਂ ਪਰਵਾਰ ਹੈਮਬਰਗ ਰਹਿਣ ਚਲੇ ਗਏ, ਕਿਉਂਕਿ ਉਸਦੇ ਪਿਤਾ, ਰੋਸ਼ਨਖਿਆਲੀ ਅਤੇ ਰਿਪਬਲਿਕਨ ਆਦਰਸ਼ਾਂ ਦਾ ਸਮਰਥਕ ਸੀ, ਉਸਨੇ ਪਰੂਸੀਅਨ ਅਨੈਕਸੇਸ਼ਨ ਤੋਂ ਬਾਅਦ ਡੈਨਜ਼ਿਗ ਨੂੰ ਅਯੋਗ ਸਮਝਿਆ। ਉਸ ਦਾ ਪਿਤਾ ਚਾਹੁੰਦਾ ਸੀ ਕਿ ਆਰਥਰ ਉਸ ਵਰਗਾ ਹੀ ਇੱਕ ਬ੍ਰਹਿਮੰਡੀ ਵਪਾਰੀ ਬਣੇ ਅਤੇ ਇਸ ਲਈ ਉਸ ਨੇ ਆਪਣੀ ਜਵਾਨੀ ਵਿੱਚ ਆਰਥਰ ਨੇ ਖ਼ੂਬ ਯਾਤਰਾ ਕੀਤੀ। ਉਸ ਦੇ ਪਿਤਾ ਨੇ ਆਰਥਰ ਨੂੰ ਇੱਕ ਫਰਾਂਸੀਸੀ ਪਰਿਵਾਰ ਨਾਲ ਦੋ ਸਾਲਾਂ ਲਈ ਰਹਿਣ ਦਾ ਇੰਤਜ਼ਾਮ ਕੀਤਾ ਜਦੋਂ ਉਹ ਨੌਂ ਸਾਲ ਦਾ ਸੀ, ਜਿਸ ਨੇ ਆਰਥਰ ਨੂੰ ਫ੍ਰੈਂਚ ਭਾਸ਼ਾ ਵਿੱਚ ਰਵਾਂ ਬਣਨ ਦਾ ਮੌਕਾ ਦਿੱਤਾ। ਛੋਟੀ ਉਮਰ ਤੋਂ ਹੀ ਆਰਥਰ ਇੱਕ ਵਿਦਵਾਨ ਦੀ ਜ਼ਿੰਦਗੀ ਬਤੀਤ ਕਰਨਾ ਚਾਹੁੰਦਾ ਸੀ। ਉਸ ਤੇ ਆਪਣਾ ਕੈਰੀਅਰ ਠੋਸਣ ਦੀ ਬਜਾਏ, ਹੈਨਰਿਖ਼ ਨੇ ਆਰਥਰ ਦੇ ਅੱਗੇ ਇੱਕ ਪ੍ਰਸਤਾਵ ਰੱਖਿਆ: ਮੁੰਡਾ ਜਾਂ ਤਾਂ ਆਪਣੇ ਮਾਤਾ-ਪਿਤਾ ਨਾਲ ਯੂਰਪ ਦੇ ਦੌਰੇ ਤੇ ਜਾ ਸਕਦਾ ਸੀ, ਜਿਸ ਦੇ ਬਾਅਦ ਉਹ ਕਿਸੇ ਵਪਾਰੀ ਨਾਲ ਵਪਾਰ ਸਿਖੇਗਾ, ਜਾਂ ਉਹ ਯੂਨੀਵਰਸਿਟੀ ਵਿੱਚ ਜਾਣ ਲਈ ਤਿਆਰੀ ਕਰਨ ਲਈ ਇੱਕ ਜਿਮਨੇਜ਼ੀਅਮ ਵਿੱਚ ਜਾ ਸਕਦਾ ਸੀ। ਆਰਥਰ ਨੇ ਪਹਿਲੇ ਵਾਲਾ ਵਿਕਲਪ ਚੁਣਿਆ, ਅਤੇ ਇਸ ਯਾਤਰਾ ਦੌਰਾਨ ਉਸ ਨੇ ਗਰੀਬਾਂ ਦੀ ਬੇਹੱਦ ਬੁਰੀ ਹਾਲਤ ਅੱਖੀਂ ਦੇਖੀ ਅਤੇ ਇਸ ਨੇ ਉਸ ਦੇ ਨਿਰਾਸ਼ਾਵਾਦੀ ਦਾਰਸ਼ਨਿਕ ਦੁਨੀਆਵੀ ਨਜ਼ਰੀਏ ਨੂੰ ਢਾਲਣ ਕੰਮ ਕੀਤਾ।

ਹਵਾਲੇ

ਸੋਧੋ- ↑ German Idealism on the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- ↑ Idealism (Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy)

- ↑ Arthur Schopenhauer (1788—1860) (Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy)

- ↑ Beiser reviews the commonly held position that Schopenhauer was a transcendental idealist and he rejects it: "Though it is deeply heretical from the standpoint of transcendental idealism, Schopenhauer's objective standpoint involves a form of transcendental realism, i.e. the assumption of the independent reality of the world of experience." (Beiser 2016, p. 40)

- ↑ Schopenhauer, Arthur. Parerga and Paralipomena, Short Philosophical Essays, Vol. 2, Oxford University Press, 2000, Ch. XII: "Additional Remarks on the Doctrine of the Suffering of the World", § 149, p. 292; Schopenhauer, Arthur. Studies in Pessimism: The Essays. The Pennsylvania State University, 2005, p. 7.

- ↑ Arthur Schopenhauer, Arthur Schopenhauer: The World as Will and Presentation, Volume 1, Routledge, 2016, p. 211: "the world [is a] mere presentation, object for a subject..."

- ↑ Lennart Svensson, Borderline: A Traditionalist Outlook for Modern Man, Numen Books, 2015, p. 71: "[Schopenhauer] said that 'the world is our conception'. A world without a perceiver would in that case be an impossibility. But we can—he said—gain knowledge about Essential Reality for looking into ourselves, by introspection. ... This is one of many examples of the anthropic principle. The world is there for the sake of man."

- ↑ Nakli itihaas jo likheya geya hai kade na vaapriya jo ohna de base te, saade te saada itihaas bna ke ehna ne thop dittiyan. anglo sikh war te ek c te 3-4 jagaha te kiwe chal rahi c ikko war utto saal 1848 jdo angrej sara punjab 1845 ch apne under kar chukke c te oh 1848 ch kihna nal jang ladd rahe c. Script error: The function "citation198.168.27.221 14:54, 13 ਦਸੰਬਰ 2024 (UTC)'"`UNIQ--ref-00000023-QINU`"'</ref>" does not exist.

- ↑ Howard, Don A. (December 2005), "Albert Einstein as a Philosopher of Science" (PDF), Physics Today, 58 (12), American Institute of Physics: 34–40, Bibcode:2005PhT....58l..34H, doi:10.1063/1.2169442, retrieved 2015-03-08 – via University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame, IN, author's personal webpage,

From Schopenhauer he had learned to regard the independence of spatially separated systems as, virtually, a necessary a priori assumption ... Einstein regarded his separation principle, descended from Schopenhauer's principium individuationis, as virtually an axiom for any future fundamental physics. ... Schopenhauer stressed the essential structuring role of space and time in individuating physical systems and their evolving states. This view implies that difference of location suffices to make two systems different in the sense that each has its own real physical state, independent of the state of the other. For Schopenhauer, the mutual independence of spatially separated systems was a necessary a priori truth.

- ↑ "John Gray: Forget everything you know— Profiles, People". London: The Independent. 3 September 2002. Archived from the original on 9 April 2010. Retrieved 12 March 2010.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ↑ Nakli itihaas jo likheya geya hai kade na vaapriya jo ohna de base te, saade te saada itihaas bna ke ehna ne thop dittiyan. anglo sikh war te ek c te 3-4 jagaha te kiwe chal rahi c ikko war utto saal 1848 jdo angrej sara punjab 1845 ch apne under kar chukke c te oh 1848 ch kihna nal jang ladd rahe c. Script error: The function "citation198.168.27.221 14:54, 13 ਦਸੰਬਰ 2024 (UTC)'"`UNIQ--ref-00000027-QINU`"'</ref>" does not exist.

- ↑ Nakli itihaas jo likheya geya hai kade na vaapriya jo ohna de base te, saade te saada itihaas bna ke ehna ne thop dittiyan. anglo sikh war te ek c te 3-4 jagaha te kiwe chal rahi c ikko war utto saal 1848 jdo angrej sara punjab 1845 ch apne under kar chukke c te oh 1848 ch kihna nal jang ladd rahe c. Script error: The function "citation198.168.27.221 14:54, 13 ਦਸੰਬਰ 2024 (UTC)'"`UNIQ--ref-00000028-QINU`"'</ref>" does not exist.

- ↑ Nakli itihaas jo likheya geya hai kade na vaapriya jo ohna de base te, saade te saada itihaas bna ke ehna ne thop dittiyan. anglo sikh war te ek c te 3-4 jagaha te kiwe chal rahi c ikko war utto saal 1848 jdo angrej sara punjab 1845 ch apne under kar chukke c te oh 1848 ch kihna nal jang ladd rahe c. Script error: The function "citation198.168.27.221 14:54, 13 ਦਸੰਬਰ 2024 (UTC)'"`UNIQ--ref-00000029-QINU`"'</ref>" does not exist., Ch. 16

- ↑ Nakli itihaas jo likheya geya hai kade na vaapriya jo ohna de base te, saade te saada itihaas bna ke ehna ne thop dittiyan. anglo sikh war te ek c te 3-4 jagaha te kiwe chal rahi c ikko war utto saal 1848 jdo angrej sara punjab 1845 ch apne under kar chukke c te oh 1848 ch kihna nal jang ladd rahe c. Script error: The function "citation198.168.27.221 14:54, 13 ਦਸੰਬਰ 2024 (UTC)'"`UNIQ--ref-0000002A-QINU`"'</ref>" does not exist.

- ↑ Nakli itihaas jo likheya geya hai kade na vaapriya jo ohna de base te, saade te saada itihaas bna ke ehna ne thop dittiyan. anglo sikh war te ek c te 3-4 jagaha te kiwe chal rahi c ikko war utto saal 1848 jdo angrej sara punjab 1845 ch apne under kar chukke c te oh 1848 ch kihna nal jang ladd rahe c. Script error: The function "citation198.168.27.221 14:54, 13 ਦਸੰਬਰ 2024 (UTC)'"`UNIQ--ref-0000002B-QINU`"'</ref>" does not exist.

- ↑ The Oxford Encyclopedic English Dictionary. 'Schopenhauer': Oxford University Press. 1991. p. 1298. ISBN 978-0-19-861248-3.

- ↑ Nakli itihaas jo likheya geya hai kade na vaapriya jo ohna de base te, saade te saada itihaas bna ke ehna ne thop dittiyan. anglo sikh war te ek c te 3-4 jagaha te kiwe chal rahi c ikko war utto saal 1848 jdo angrej sara punjab 1845 ch apne under kar chukke c te oh 1848 ch kihna nal jang ladd rahe c. Script error: The function "citation198.168.27.221 14:54, 13 ਦਸੰਬਰ 2024 (UTC)'"`UNIQ--ref-0000002D-QINU`"'</ref>" does not exist.

- ↑ Studies in Pessimism – audiobook from LibriVox.

- ↑ Nakli itihaas jo likheya geya hai kade na vaapriya jo ohna de base te, saade te saada itihaas bna ke ehna ne thop dittiyan. anglo sikh war te ek c te 3-4 jagaha te kiwe chal rahi c ikko war utto saal 1848 jdo angrej sara punjab 1845 ch apne under kar chukke c te oh 1848 ch kihna nal jang ladd rahe c. Script error: The function "citation198.168.27.221 14:54, 13 ਦਸੰਬਰ 2024 (UTC)'"`UNIQ--ref-0000002E-QINU`"'</ref>" does not exist.

- ↑ Arthur Schopenhauer, The World as Will and Representation, Vol. 1, trans. E. Payne, (New York: Dover Publishing Inc., 1969), Vol. 2, Ch. 50.

- ↑ Nakli itihaas jo likheya geya hai kade na vaapriya jo ohna de base te, saade te saada itihaas bna ke ehna ne thop dittiyan. anglo sikh war te ek c te 3-4 jagaha te kiwe chal rahi c ikko war utto saal 1848 jdo angrej sara punjab 1845 ch apne under kar chukke c te oh 1848 ch kihna nal jang ladd rahe c. Script error: The function "citation198.168.27.221 14:54, 13 ਦਸੰਬਰ 2024 (UTC)'"`UNIQ--ref-0000002F-QINU`"'</ref>" does not exist.

- ↑ See the book-length study about oriental influences on the genesis of Schopenhauer's philosophy by Urs App: Schopenhauer's Compass. An Introduction to Schopenhauer's Philosophy and its Origins. Wil: UniversityMedia, 2014 (ISBN 978-3-906000-03-9)

- ↑ Nakli itihaas jo likheya geya hai kade na vaapriya jo ohna de base te, saade te saada itihaas bna ke ehna ne thop dittiyan. anglo sikh war te ek c te 3-4 jagaha te kiwe chal rahi c ikko war utto saal 1848 jdo angrej sara punjab 1845 ch apne under kar chukke c te oh 1848 ch kihna nal jang ladd rahe c. Script error: The function "citation198.168.27.221 14:54, 13 ਦਸੰਬਰ 2024 (UTC)'"`UNIQ--ref-00000031-QINU`"'</ref>" does not exist.

<ref> tag defined in <references> has no name attribute.